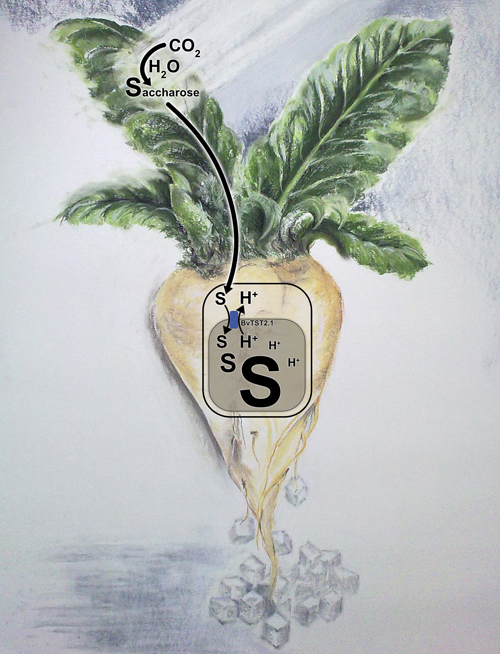

Why do sugar beets contain sugar in the first place? This mystery has finally been solved: Research teams from Germany have identified the responsible sugar transporter. This discovery is a strong impetus to breed enhanced crops.

Sugar beet (Beta vulgaris) provides around one third of the sugar consumed worldwide. The bulbous plants also serve as a significant source of bioenergy in the form of ethanol.

“The sugar beet was originally used as a leafy vegetable,” says Professor Rainer Hedrich, a plant scientist of the University of Würzburg. Due to breeding efforts in Europe since the late 18th century, the plants have become real sugar factories: “Our high-performance sugar beets contain as much as 2.3 kilogrammes of sugar in ten kilogrammes of beet.” But the principle of sugar storage in the plants was unknown until recently.

Specific transporter identified

Hedrich’s group has now solved this question in collaboration with scientists from the universities of Erlangen, Kaiserslautern and Cologne and with teams from KWS Saat AG and Südzucker AG: Most of the sugar is concentrated in the taproot as sucrose where it accumulates in the vacuoles. A transport protein called BvTST2.1 acts as a vacuolar sucrose importer.

The researchers have now discovered this transporter and characterised its molecular structure. They believe that the new findings could help to increase sugar yields in sugar beet, sugar cane or other sugar-storing crops by modifying the plants to boost the amount of transporters they contain. The research results are presented in the renowned science magazine “Nature Plants”. The project was funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF).

Experiments led the way to success

How did the research team obtain its findings? First, they determined the developmental stage during which the beet accumulates sugar. Next, the scientists identified which proteins were increasingly produced during the accumulation phase. Using genome databases, they then determined the genes eligible as potential sugar transporters.

This shifted the focus on one “prime suspect”, namely the transport protein BvTST2.1. But how to find out whether this transporter is actually capable of importing sucrose into the vacuole? At this point, the biophysical expertise of Hedrich’s team came into play: “We benefited from the fact that the leaf cells do not produce the transport protein of the sugar beet vacuole. So we inserted the beet transporter gene bvtst2.1 into the leaf cells, isolated their vacuoles and measured whether and how the beet protein transports sugar,” the professor explains.

Using the patch-clamp method, the scientists demonstrated that the beet transporter selectively imports sucrose into the vacuole and exports protons from the vacuole in turn. This coupled mechanism ultimately results in sugar accumulating in the beet vacuoles where it can reach peak concentrations of 23 percent.

Potential benefits of the new findings

In order to further improve sugar beet crops in terms of sugar storage, the BvTST2.1 transporter has to be tackled inside the sugar beet in a next step: For this purpose, sugar beets containing different amounts of the transporter need to be produced in the lab. Subsequently, the researchers have to observe which impact the transporter dosage has on the beet’s sugar content.

“If these tests back our assumptions, it will be possible to breed beets with higher transporter content,” Hedrich predicts. Ultimately, this could yield a new generation of beet crops which store more sugar or which start to store sugar earlier in the year.

“Identification of transporter responsible for sucrose accumulation in sugar beet taproots“, Benjamin Jung, Frank Ludewig, Alexander Schulz, Garvin Meißner, Nicole Wöstefeld, Ulf-Ingo Flügge, Benjamin Pommerrenig, Petra Wirsching, Norbert Sauer, Wolfgang Koch, Frederik Sommer, Timo Mühlhaus, Michael Schroda, Tracey Ann Cuin, Dorothea Graus, Irene Marten, Rainer Hedrich, and H. Ekkehard Neuhaus, Nature Plants, 2015, January 8, DOI: 10.1038/nplants.2014.1

Contact

Prof. Dr. Rainer Hedrich

Department of Botany I of the University of Würzburg

Phone: +49 931 31-86100

E-Mail: hedrich@botanik.uni-wuerzburg.de

Author

Robert Emmerich

Source

University of Würzburg, press release, 2015-01-08.

Supplier

Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF)

Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg

Nature Plants - Journal

Technische Universität Kaiserslautern

Universität Würzburg

Universität zu Köln

Share

Renewable Carbon News – Daily Newsletter

Subscribe to our daily email newsletter – the world's leading newsletter on renewable materials and chemicals