Introduction

In recent years, Polylactic Acid (PLA) has emerged as one of the most promising and commercially relevant bioplastics in the global polymer industry. Derived primarily from renewable agricultural resources such as corn, sugarcane, or cassava, PLA represents a viable alternative to traditional petrochemical-based plastics, combining environmental sustainability, regulatory compliance, and competitive performance in a broad range of applications. Its biodegradability, compostability, and reduced carbon footprint have positioned PLA as a cornerstone of the circular bioeconomy and a key material in the transition toward low-carbon and resource-efficient manufacturing systems.

This report aims to deliver an overview of the current state and future trajectory of PLA, detailing its production technologies, industrial players, feedstock sources, market evolution, sustainability profile and some of the innovatives that are currently on going, such as BeonNAT contributions to smart and sustainable development of PLA from marginal biomass.

Production Processes

PLA is made by polymerizing lactic acid (or its cyclic dimer, lactide) obtained from fermented biomass (corn, sugarcane, etc.). In practice almost all PLA is produced by ring-opening polymerization (ROP) of purified lactide, using metal catalysts (e.g. tin octoate, zinc) to yield high-molecular-weight PLA. Modern plants integrate starch/sugar pretreatment, fermentation to lactic acid, lactide purification, and polymerization units.

For example, NatureWorks’ process (Ingeo™) uses corn starch: starch is hydrolyzed to glucose, fermented to L-lactic acid, purified/distilled to lactide, then polymerized continuously into PLA pellets 1 (Yu, Y., Flury, M. Unlocking the Potentials of Biodegradable Plastics with Proper Management and Evaluation at Environmentally Relevant Concentrations2.

Engineering features include large fermenters, distillation/crystallization equipment (for lactide), and polymer reactors (often with twin-screw extrusion or batch reactors). Copolymerization or blending steps produce specialized PLA grades (e.g. high-heat grades).

Operating costs are dominated by feedstock (e.g. sugar or corn) and energy; the complex multi-step process yields a PLA cost still above conventional plastics3. Some analysis markets note that PLA’s higher cost arises from its bio-based feedstocks and complex fermentation/polymerization steps requiring precise conditions.

Environmental Impact

PLA is fully bio-based and certified industrial-compostable (ASTM D6400/EN13432). LCA studies show PLA can emit less net CO₂ than petro-plastics (~75% lower lifetime carbon footprint4. However, PLA’s biodegradation requires controlled conditions, usually requiring industrial composting facilities as well as in thermophilic anaerobic digesters (not in soil or ambient environments)5. Thus end-of-life requires proper composting or recycling. Overall, PLA’s environmental profile is considered superior in terms of renewable carbon use, but its actual GHG savings hinge on agriculture practices, and like any plastic it must be managed via composting or mechanical/chemical recycling.

Economic Factors: PLA plants are capital-intensive. One techno-economic analysis estimated CAPEX for a 2 kt/yr plant at around $10.35M (and a PLA sale price of $1,400/t, yielding a 9.5-year payback)3. Costs include fermenters, distillation, reactors, crystallizers, and waste treatment. Key OPEX drivers are feedstock (corn or sugar), energy, and catalysts. Worldwide feedstock prices (sugar, corn) therefore strongly influence PLA costs.

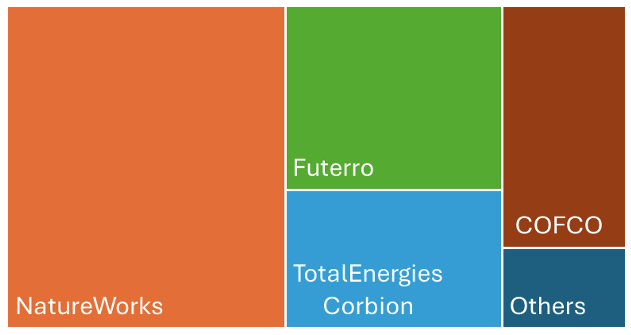

Key Global Manufacturers and Capacities

The global PLA industry is concentrated in a few large producers. NatureWorks LLC is dominant: it currently makes ~150 kt/yr Ingeo PLA (U.S. plant) and is commissioning a new 75 kt/yr integrated biorefinery in Thailand according to few sources1,7. The Thai plant combines lactic acid fermentation, lactide production, and polymerization, and will support high-heat PLA grades via a melt-crystallizer1. TotalEnergies Corbion (Netherlands/Thailand) produces its Luminy PLA at ~75 kt/yr also using sugarcane as feedstock7.

Futerro (Belgium) built an ~100 kt/yr PLA line in China (through Chinese partners) in 20218, and is now funding a 75 kt/yr PLA biorefinery in France (Normandy) targeting ~2027 startup. In China, several firms (e.g. COFCO Biochemical, Zhejiang Hisun, WeforYou) run smaller lactide and PLA plants (often 5–30 kt/yr scale); notably COFCO is building a 30 kt/yr lactide unit to feed PLA production9.

Other players include Galactic (Belgium), Ampliqon/BASF (Denmark), and Japanese companies (Teijin, Unitika) with niche PLA capacities. In total, global PLA production capacity exceeded roughly 700 kt/yr by 20226 .

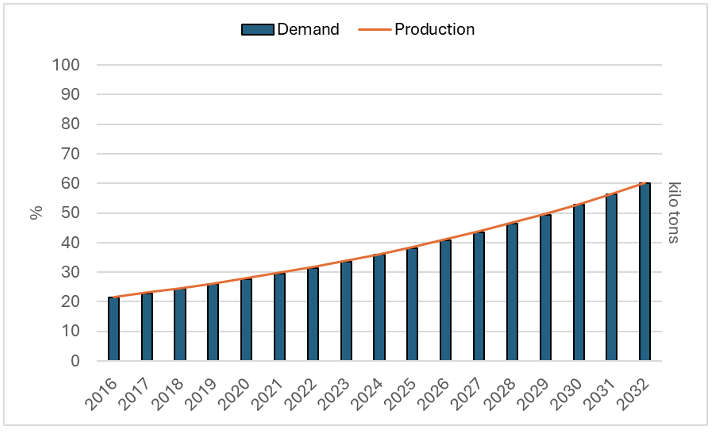

End-Use Markets and Demand

PLA’s largest market by far is packaging and disposable tableware. Single-use food packaging (cups, containers, cutlery) accounts for roughly half or more of global PLA use7. For example, one analysis estimated packaging at ~60% of PLA demand is the largest end use of PLA7. Consumer and retail applications (coffee capsules, films, bottles, 3D-print filaments, toys) form the next largest category (on the order of ~15–25% of demand).

PLA fibers/nonwovens (textiles, hygiene products like diapers and wipes) and agricultural films/mulch cover smaller shares. Medical uses (biodegradable implants, drug-delivery devices, sutures) are niche but growing. In sum, packaging dominates, followed by consumer goods/3D printing, with textiles, agriculture, medical as emerging segments.

Lactic Acid Feedstocks and Supply Chain

PLA is produced from lactic acid (or lactide) derived almost exclusively by microbial fermentation of carbohydrates. Major lactic-acid feedstocks are corn (starch) and sugarcane/sugar beet.

In 2022, research reports showed sugarcane contributed ~38% of lactic acid feedstock and corn was second-largest10. Roughly 90%+ of lactic acid is produced by submerged fermentation (e.g. Lactobacillus fermentation).

Some projects target lignocellulosic or non-food biomass: for example, the Praj–Thyssenkrupp process is touted as adaptable to “any agricultural feedstock containing starch or sugar, including second-generation feedstocks” 11. Major lactic acid players often vertically integrate into PLA: e.g. Corbion sells lactic acid and PLA (Luminy), while Galactic and Futerro also supply monomers and polymers.

Alternative Commercial Methods for PLA Synthesis

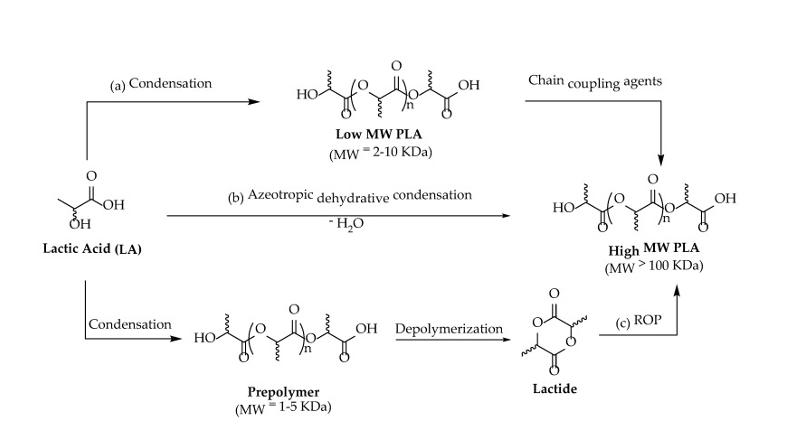

As shown in Scheme 1, direct condensation yields low-MW PLA (typically a few tens of kDa) unless chain extenders are used12. Azeotropic dehydration (Mitsui’s method) drives water off in a refluxing high-boiling solvent to give much higher-MW PLA (≥300 kDa) without coupling agents 12,13. ROP (the standard industrial route) first makes lactide and then polymerizes it to high-MW PLA.

Direct (Melt) Polycondensation of Lactic Acid

In this one-step method, fermented lactic acid is heated under vacuum (often in a twin-screw extruder or reactor) so that it condenses into PLA, continuously removing water. No intermediate lactide step is used. In practice, this yields oligomeric PLA with low molecular weight (<50–100 kDa) and low strength12.

To raise molecular weight, producers may add chain-coupling agents or multifunctional monomers during or after condensation. This route is conceptually simpler, and capital costs are lower than ROP (no need for a separate lactide purification train), but it is difficult to reach high-MW PLA without additives. As a result, almost all large PLA plants still use ROP, and pure one-step condensation is seldom used at scale. No major Western producer runs a purely melt-polycondensation PLA plant today. Some smaller Chinese and Japanese companies have experimented with this route, but typically they switch to a two-step (lactide) process or use solid-state polycondensation afterwards to boost Mw.

Azeotropic (Solvent) Polycondensation of Lactic Acid

This variant (pioneered by Mitsui Chemicals in Japan) polymerizes lactic acid in a high-boiling inert solvent (e.g. diphenyl ether) under reflux and vacuum. The key is that water of condensation is continuously removed by the solvent (azeotropically) and by vacuum. Mitsui’s patented process (circa 1994–2000) achieves very high Mw PLA (weight-average Mw ∼200–300 kDa) in a single step, without the need for chain extenders.

Typically, a tin catalyst is used, and the reaction runs for >30 hours. The result is a high-purity, high-Mw PLA directly from lactic acid. Mitsui documented this in the early 2000s, claiming Mw up to 330,000.

Mitsui Chemicals (Japan) reported using this one-step solution route to make their high-Mw PLA (branded LACEA). It is believed that Mitsui’s own PLA plants (if still active) relied on this method, though no recent corporate disclosures confirm current use. No other major PLA maker has publicly announced use of this route; it appears to remain mostly a proprietary Japanese technology.

Comparison to ROP

In summary, both alternative routes sacrifice some aspects of the standard lactide-ROP process. Direct condensation is cheapest in principle but yields lower-performance PLA and requires extra chemistry to achieve acceptable Mw. Azeotropic condensation can attain very high Mw without extenders, but at the cost of complexity, solvent use, and long reaction times. By contrast, the mature ROP method (lactide preparation & polymerization) yields high-Mw, high-quality PLA efficiently and in continuous operation12. It is the basis of nearly all large commercial PLA plants (e.g. NatureWorks, Total Corbion, Jindan, Emirates Biotech)14. ROP’s drawbacks are the need to purify lactide (energy-intensive) and use metal catalysts, but industry has optimized these steps for cost and scale.

Other synthetic routes (e.g. direct microbial/enzymatic PLA biosynthesis) have been reported in academic literature, but none are yet commercial15. For example, Carbios has demonstrated an in vivo enzyme route to PLA, but as of 2025 this remains at pilot scale and is not deployed industrially.

The role of alternative feedstocks and marginal land cultivation

The growing demand for sustainable materials has underscored the importance of broadening the feedstock base for biopolymer production. As previously exposed, traditional PLA manufacturing relies heavily on carbohydrate-rich crops such as corn and sugarcane, which, while renewable, compete with food and feed uses and depend on fertile land and intensive agricultural inputs. To overcome these limitations, alternative biomass sources – including forest residues, energy crops, and industrial by-products – are being explored as more sustainable raw materials. The concept of smart cultivation of marginal and underutilized lands has emerged as a key innovation within the European bioeconomy.

By cultivating non-food, fast-growing woody and herbaceous species on degraded or low-productivity soils, industries can generate a continuous and regionally adapted biomass supply without disrupting agricultural production or biodiversity. Such approaches enhance land-use efficiency, reduce carbon emissions, and support rural development, all while providing lignocellulosic feedstocks suitable for conversion into bio-based chemicals and materials – including lactic acid and PLA. This strategy is central to several EU research initiatives, among which the BeonNAT Project stands out as a pioneering example.

Innovation case study: PLA bottles from forest biomass

One of the most innovative developments in recent years in the European bioplastics sector has been the successful production of PLA bottles derived from forest biomass, achieved under the framework of the BeonNAT Project (Horizon 2020, Grant Agreement No. 887917) and a consortium of research and industrial partners. This initiative represents a key advance in diversifying the feedstock sources for biopolymer production, moving beyond conventional carbohydrate crops (corn, sugarcane) toward non-food lignocellulosic biomass obtained from marginal and underutilized lands.

The process began with the selection and design of forest species optimized for lactic acid production. BeonNAT focused on identifying fast-growing, high-cellulose content species, capable of thriving on poor soils with minimal agricultural inputs. Once the optimal species were defined, biomass recovery operations were carried out, involving sustainable harvesting and conditioning to ensure the material met the specifications required for biochemical conversion.

The process

The recovered lignocellulosic biomass underwent mechanical and chemical pretreatment to fractionate cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin components. The pretreatment stage, using dilute acid hydrolysis and steam explosion techniques, was essential to enhance the accessibility of fermentable sugars. Process optimization focused on maximizing glucose yield while minimizing inhibitor formation, thereby improving the overall efficiency of subsequent fermentation.

Following pretreatment, the hydrolysates rich in fermentable sugars were subjected to microbial fermentation for the production of lactic acid (LA) with high optical purity, an essential parameter for obtaining high-molecular-weight PLA. The fermentation process was fine-tuned to achieve higher productivity and yield, using advanced bioreactor control strategies and nutrient recycling to reduce costs and waste generation.

AIMPLAS used the purified lactic acid obtained from fermentation to dimerize it into lactide through a controlled dehydration and polycondensation sequence. The resulting lactide monomer, predominantly in the L-isomeric form, was then polymerized via ring-opening polymerization (ROP), the standard industrial route for high-performance PLA by reactive extrusion. The polymerization was catalyzed under controlled conditions to achieve high molecular weight in a continuous process.

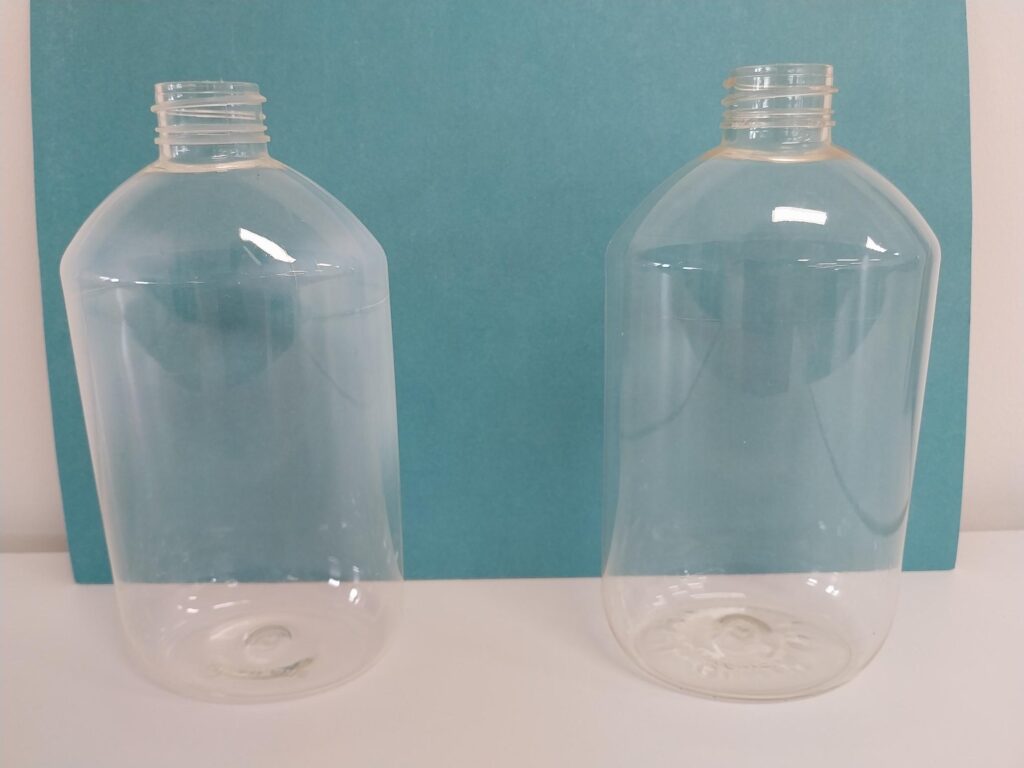

The resulting PLA was compounded and compared with injection molding commercial grade PLA to fabricate biobased and compostable bottles. These bottles demonstrated properties and transparency comparable to those of conventional packaging, while potentially being fully biodegradable under industrial composting conditions.

This development represents a closed-loop, bio-based alternative to fossil-derived plastics, utilizing forest biomass residues as feedstock rather than food crops—an important step toward improving the sustainability profile of PLA and aligning with the EU Bioeconomy Strategy.

Conclusion

The BeonNAT project, illustrates a complete value chain for the conversion of lignocellulosic biomass into high-value bioplastics. The process integrates feedstock optimization, biochemical conversion, and polymer synthesis, achieving proof-of-concept for PLA bottles that meet both technical performance and environmental sustainability standards. This advancement not only broadens the potential raw materials for PLA production but also reinforces the feasibility of forest-based biorefineries within Europe’s growing circular economy framework.

BeonNAT is funded by the Bio-Based Industries Joint Undertaking (BBI-JU) with grant agreement number 887917. BBI-JU is supported by the Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme of the European Union and the Bio-Based Industries Consortium.

References

1. NatureWorks Announces Next Phase of Construction on New Fully Integrated Ingeo PLA Biopolymer Manufacturing Facility in Thailand. https://www.natureworksllc.com/about-natureworks/news/press-releases/2023/2023-10-18-natureworks-announces-next-phase-of-construction-thailand.

2. Yu, Y. & Flury, M. Unlocking the Potentials of Biodegradable Plastics with Proper Management and Evaluation at Environmentally Relevant Concentrations. npj Materials Sustainability 2, (2024).

3. Rueda-Duran, C. A., Ortiz-Sanchez, M. & Cardona-Alzate, C. A. Detailed economic assessment of polylactic acid production by using glucose platform: sugarcane bagasse, coffee cut stems, and plantain peels as possible raw materials. Biomass Convers Biorefin 12, 4419–4434 (2022).

4. Benavides, P. T., Lee, U. & Zarè-Mehrjerdi, O. Life cycle greenhouse gas emissions and energy use of polylactic acid, bio-derived polyethylene, and fossil-derived polyethylene. J Clean Prod 277, (2020).

5. Fambri, L., Dorigato, A. & Pegoretti, A. Role of surface-treated silica nanoparticles on the thermo-mechanical behavior of poly(Lactide). Applied Sciences (Switzerland) 10, 1–20 (2020).

6. Polylactic Acid (PLA) Market Analysis By Demand, By Region, By Applications and Forecast Report Till 2036. https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/polylactic-acid-pla-market (2024).

7. Inside the debate over PLA, the packaging industry’s favorite bioplastic. https://www.packagingdive.com/news/polylactic-acid-pla-bioplastic-compostable-packaging/728875/ (2024).

8. Futerro closes its first external fund-raising for its biorefinery project in Europe. https://www.futerro.com/futerro-closes-its-first-external-fund-raising-for-its-biorefinery-project-in-europe/.

9. COFCO Technology (000930.SZ): The 30,000 tons/year lactide project is currently under main construction. https://www.moomoo.com/news/post/27283751/cofco-technology-000930-sz-the-30000-tons-year-lactide-project.

10. Leading Companies in the Global Lactic Acid Market, Including Futerro, BASF, Galactic, and Corbion, Expected to Contribute to Market Growth. https://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2023/07/27/2711984/28124/en/Leading-Companies-in-the-Global-Lactic-Acid-Market-Including-Futerro-BASF-Galactic-and-Corbion-Expected-to-Contribute-to-Market-Growth.html (2023).

11. Praj Industries and thyssenkrupp Uhde partner on PLA production. https://www.thyssenkrupp-uhde.com/en/media/press-releases/press-detail/thyssenkrupp-uhde-and-praj-industries-ltd-join-forces-to-revolutionize-polylactic-acid-production-and-circular-economy-297517 (2025).

12. Lombardi, A. et al. Natural Active Ingredients for Poly (Lactic Acid)-Based Materials: State of the Art and Perspectives. Antioxidants vol. 11 Preprint at https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox11102074 (2022).

13. Garlotta, D. A literature review of poly(lactic acid). J Polym Environ 9, 63–84 (2001).

14. Emirates Biotech Selected Sulzer Technology to Build World’s Largest Polylactic Acid Production Facility. https://www.sulzer.com/en/shared/news/241210-emirates-biotech-selected-sulzer-technology-to-build-worlds-largest-pla-facility (2024).

15. CARBIOS opens a new biological pathway with its one-step PLA production process. CARBIOS opens a new biological pathway with its one-step PLA production process. (2016).

Author

Carlos Fernández Ruiz (AIMPLAS)

Source

AIMPLAS, original text, 2025-11-07.

Supplier

AIMPLAS (Asociación de Investigación de Materiales Plásticos y Conexas)

Ampliqon

BASF Corporation (US)

Bio Based Industries Joint Undertaking (BBI JU)

Bio-based Industries Consortium (BIC)

COFCO Ltd.

European Union

Futerro

Galactic

Mitsui Chemicals

NatureWorks LLC

Teijin Ltd.

TotalEnergies Corbion

UNITIKA Ltd.

Share

Renewable Carbon News – Daily Newsletter

Subscribe to our daily email newsletter – the world's leading newsletter on renewable materials and chemicals