We need plastics for the critical services they provide. Plastics are now at the very base of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, underpinning modern healthcare, shelter, food, clothing, and even the mattresses we sleep on. They’re fundamental to future energy systems. We might not need a plastic straw in every drink, but we don’t know how to make a wind turbine without plastics.

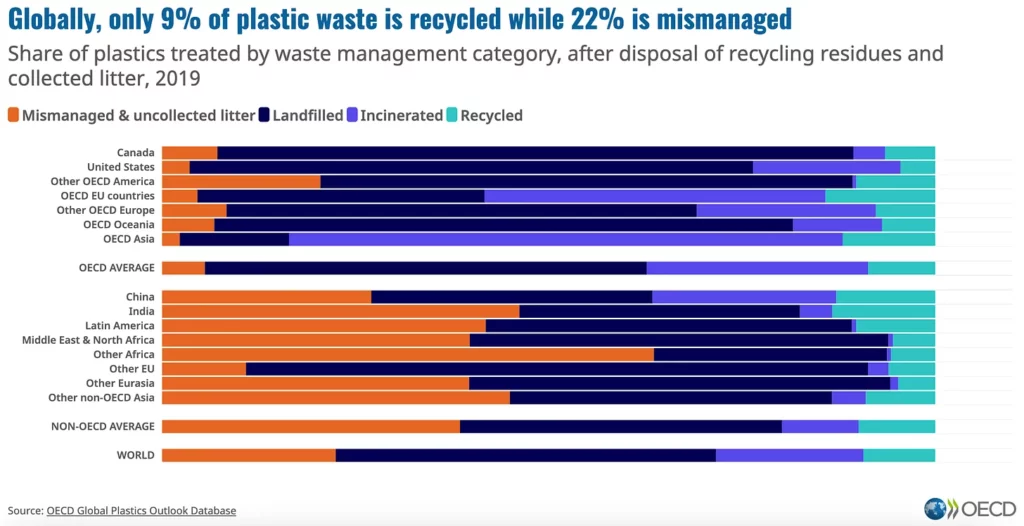

And yet, the current system is fundamentally unsustainable. Plastics were designed for a linear economy, made to be used and thrown away. Only 9% of plastic around the world is recycled (OECD 2022). In some regions, more than half of plastic waste is mismanaged, ending up as pollution in the environment. The very characteristics that make plastics essential—strength, durability, light weight—make them an environmental nightmare.

As if that’s not enough of a problem, plastics are made mostly from fossil fuels. As we move towards Net Zero, the use of fossil fuels for chemicals, including plastics, has got to stop. RCI has already estimated that, by 2050, we should be getting 20% of our carbon from bio-based sources, 25% directly from CO2, 50% from recycling of those renewable sources, and 5% from recycling of fossil feedstocks. There’s no space in this scenario for virgin fossil fuel plastics.

Recycling plastics leads to a buildup of contaminants

There’s a major problem with the fundamental concept of plastics recycling: we don’t know what’s in recycled plastics. We don’t even really know what’s in virgin plastics, since the supply chain is so opaque. When you buy a plastic toy, you’re not told what the main polymer is, much less anything about additives or contaminants. When you buy recycled plastic, which may have come from a variety of virgin sources and been processed through multiple facilities and multiple methods, the problem is compounded.

A new paper from the University of Gothenburg puts this problem under the spotlight. The team analysed 28 samples of recycled HDPE pellets and managed to quantify 491 organic chemical compounds. Since there are currently 13,000 chemicals known to be used in plastics production, that’s not surprising. A third of the chemicals detected were pesticides and biocides. Another 18% were pharmaceuticals, 13% were industrial chemicals, and less than 10% were the expected plastic additives.

The highest concentrations found were for deliberate additives, rather than accidental biocides, but it serves as a warning of the problem with the plastics supply chain. It’s easy to see how this cocktail of additional chemicals could pose a problem if they make their way into, for example, children’s toys.

As more data like this comes out, it is clear that the system needs to be redesigned. Plant-based plastics may be part of the solution but are unlikely to solve every problem due to other considerations, such as the extent of processing required, chemical suitability for a particular application, and the impact of land use.

There is no single solution to the plastics problem

A multi-thread approach is required to mitigate our reliance on fossil carbon for generating plastics:

- reduction of plastic usage

- renewable feedstocks

- polymer chemistry designed for recycling

- redesign or removal of additives

- comprehensive waste management systems

- improved recycling methods

- safe degradation at end of life

- supply chain transparency

We also need to ensure equal access to safe and sustainable plastics. We’re currently in a world where the toxicological burden of plastics (and chemicals) falls on the most vulnerable populations. In the end, it will be necessary to tailor plastics to specific applications and choose renewable carbon sources that can meet the specific demands of those applications. As ever, this will require greater transparency within the supply chain.

For further information on the plastics problem, see the Scientists’ Coalition for an Effective Plastics Treaty, which shares materials developed by a variety of experts.

If you are interested in championing sustainable chemistry within your organisation, join us at our upcoming free webinar:

Catalysing Change

Bringing sustainable chemistry to your boss

Thursday 2 May, 2024 | 15:00 BST / 10:00 ET

Learn how to create change from within your organisation by understanding the business value of green chemistry. Delivered by Anna Zhenova, CEO & Founder of Green Rose Chemistry, and IUK Innovate Unlocking Potential Award winner.

Author

Anna Zhenova, CEO & Founder of Green Rose Chemistry

Source

Green Rose Chemistry, original text, 2024-04.

Supplier

Green Rose Chemistry

Innovate UK

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD)

University of Gothenburg

Share

Renewable Carbon News – Daily Newsletter

Subscribe to our daily email newsletter – the world's leading newsletter on renewable materials and chemicals