Public procurement is one of the most powerful tools governments have to shape markets and accelerate change. By integrating bio-based thinking into existing green public procurement (GPP) frameworks, public authorities can directly support climate goals, strengthen regional economies, and cut dependence on fossil-based inputs. Bio-based solutions, made from renewable resources, offer practical alternatives that directly help reduce emissions, close material loops, and replace virgin raw materials with circular ones.

At the bio-based public procurement training held in Barcelona, Spain, on 4 June 2025, co-organised by the Bioregions Facility and the Government of Catalonia, experts from the Province of Zeeland joined Catalan institutions to share practical experiences and strategies. The following six insights reflect what emerged from their combined perspectives:

Key Insights

- Political will: Political leadership sets the mandate for procurement teams to prioritise sustainability and support the bioeconomy.

- Early collaboration: Engaging all relevant stakeholders early in the process helps prevent delays and leads to more effective and sustainable outcomes.

- Tools and training: The right tools, data, and training empower procurement teams to apply sustainability criteria with consistency and ease.

- Pilot projects: Pilots provide space to test innovative materials and methods while building trust and learning from experience.

- Monitoring: Measuring progress before, during, and after projects ensures impact is real, not just stated.

- Innovative legal pathways: Adaptive legal frameworks make it possible to test new approaches without fear of procedural penalties.

1. Political Will Turns Goals into Action

Core idea: Political will is the foundation for scaling bio-based procurement. It provides the leadership, resources, and space for innovation needed to align procurement with broader sustainability goals. When this commitment is reflected across public administrations, from high-level strategies to operational decisions, it enables a consistent and coordinated shift toward sustainable procurement practices.

Example:

- In Zeeland, the “Comply or Explain” policy requires suppliers to choose sustainable materials by default. If they cannot, they must formally justify their choice. This creates a cultural shift where bio-based and circular solutions become the default, not the exception.

- Catalonia’s Green Public Procurement Action Plan (2022–2025) demonstrates strong political and administrative will, with a clear target of reaching 50% green contracts. Surpassing this goal with 67% shows how defined objectives, backed by leadership, can support lasting implementation.

2. Early Collaboration Leads to Effective Implementation

Core idea: Bringing key stakeholders together early improves both the process and the outcomes. Bio-based procurement often requires new specifications, supplier adjustments, or legal clarifications. Starting the conversation late creates delays and missed opportunities.

Example:

- In Catalonia, early coordination on public construction projects between the housing corporation, architects and the construction company led to smoother tendering, faster delivery, and better sustainability performance.

- In Zeeland, efforts focused on connecting actors across the value chain, recognising that much of the environmental impact begins early in production. By engaging primary producers and supporting them to meet sustainability requirements, the region ensured upstream alignment and more effective, life cycle-based procurement.

- Zeeland also ensured early collaboration with asset owners, who play a key role in decision-making. Involving them from the start helped align priorities and made sustainable procurement outcomes more feasible and effective.

3. Tools and Training Bridge the Gap Between Policy and Practice

Core idea: Procurement teams need hands-on tools and clear guidance to act on sustainability goals; policy alone is not enough. Clear methodologies, databases, and training programmes build internal capacity and reduce resistance to change, especially when teams face unfamiliar product categories like bio-based materials.

Example:

- The province of Zeeland created an online database featuring over 1,500 verified bio-based products, reviewed by an independent commission to prevent greenwashing. This platform helps buyers and suppliers identify what is available on the market and makes it easier to incorporate bio-based alternatives into procurement.

- Zeeland also developed the Sustainable Procurement Impact Tool, which enables procurement staff and suppliers to calculate the environmental impact of tenders, including reductions in CO₂ emissions and the use of non-renewable raw materials.

- In Catalonia, the government supports implementation through structured training programmes and practical tools that help procurement teams apply environmental criteria systematically, including sector-specific guidance, contract templates, and technical resources.

4. Pilot Projects Create Space to Learn and Improve

Core idea: Pilots are an essential part of scaling sustainable procurement. They allow public authorities to test new materials, methods, and partnerships in a controlled, lower-risk setting. Importantly, the value of a pilot is not just in the outcome but in what gets shared. Whether the results are successful or mixed, transparent reporting helps others learn and adapt faster. Normalising experimentation (and even failure) is part of accelerating innovation.

Example:

- Zeeland piloted a wide range of bio-based materials in public infrastructure, including signage made from natural fibres and asphalt using lignin from the paper industry. Some pilots proved cost-effective and scalable, while others faced technical setbacks. One key learning was that bio-based solutions often require different types of maintenance and long-term planning. By monitoring performance over time and involving maintenance teams early in the process, the province was able to better anticipate needs across the full life cycle. Sharing both successes and challenges helped refine their procurement approach and offered valuable lessons to other regions.

5. Monitoring Makes Procurement Accountable

Core idea: Measuring and communicating impact is essential to make sustainability visible and credible. Monitoring should begin at the planning stage, continue through implementation, and conclude with a clear evaluation of results. It allows organisations to compare performance, share progress, and engage others more effectively. The key is to start with simple, realistic goals and support them with clear, measurable criteria.

Example:

- In Catalonia, monitoring efforts currently focus on tracking the number of tenders that include environmental criteria. While this is a useful starting point for understanding the uptake of green procurement, it does not yet capture the actual environmental impact of purchases.

- In Zeeland, the Sustainable Procurement Impact Tool1 supports project teams in setting and tracking measurable targets, such as CO₂ reductions and lower use of primary raw materials. The tool uses SDG-based indicators to align with broader policy goals and communicate progress in a language familiar to both policymakers and the public. Results are collected before, during, and after the project, then integrated into annual reporting and budgeting. This makes performance comparable across projects and helps embed sustainability into routine decision-making.

1 If you would like to learn more about this tool, please reach out to mail @ mviplatform.nl.

6. Innovative Legal Pathways Can Enable Sustainable Procurement

Core idea: Scaling sustainable and bio-based procurement requires an innovative legal environment that supports experimentation. Without space to test new approaches, rigid rules and risk-averse interpretations can prevent even the most ambitious policies from becoming practical action. Legal frameworks and internal legal teams need to enable, not block, innovation.

Example:

- In Barcelona, the municipal housing corporation has used innovation-friendly procurement rules (supported by the EU’s guidance on innovation procurement) to favour environmental performance over the lowest cost. This legal strategy embeds sustainability as a key criterion in public housing tenders, backed by strong political will. But as these methods become widespread, it remains to be seen if they are compatible with standard procurement procedures. The example underscores the need to adapt legal frameworks, so sustainability continues as a central focus beyond the initial innovation phase.

- During the training, participants emphasised the need for a regulatory sandbox, a controlled setting where procurement teams can safely test new methods. This sandbox would let authorities pilot innovative solutions, refine them through feedback, and scale successful models without compliance risks or procedural delays. It also helps reveal practical win–wins. For instance, one hospital’s switch to bio-based packaging tape not only reduced fossil-derived materials but also made recycling easier and faster for staff, a small yet valuable operational and environmental improvement.

Case Study 1: Zeeland’s Bio-asphalt Pilot

The Province of Zeeland tested a new form of asphalt where 50% of the traditional fossil-based binder was replaced with lignin, a bio-based by-product from the paper industry. The pilot aimed to reduce carbon emissions in road construction by using bio-based materials.

Although the bio-asphalt was about 20% more expensive and lasted seven years compared to the typical twelve, it was considered a success for a first trial. The project provided concrete data on performance and cost, offering a strong foundation for optimising future tenders and scaling bio-based materials more effectively. It also underscored the importance of political backing, where strong support from the province for innovation made the pilot possible.

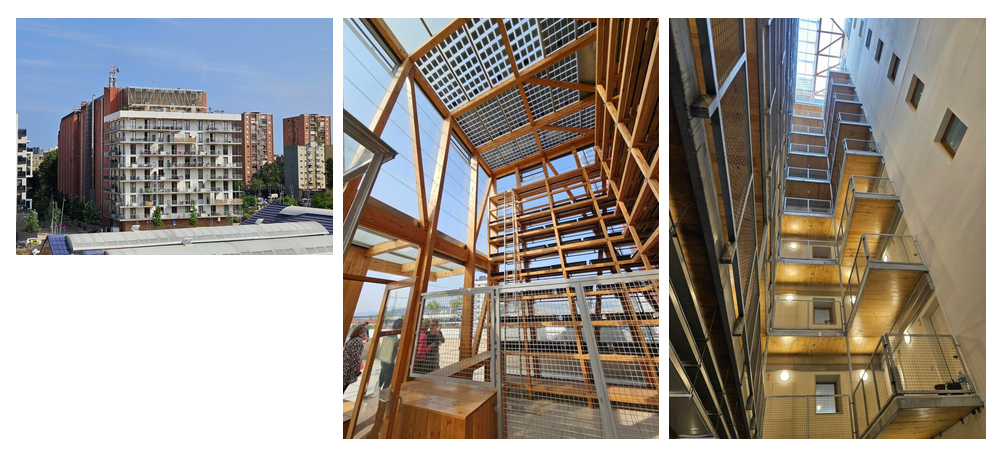

Case study 2: Bio-based Social Housing Projects in Catalonia

As part of the training, participants visited two completed social housing projects developed by IMHAB, Barcelona’s public housing agency. Built with cross-laminated timber and bio-based insulation, the buildings demonstrate how bio-based solutions can meet high-performance standards. They feature A-rated energy performance, aerothermal systems, solar panels, and rooftop vegetation.

These projects reflect key principles of effective bio-based public procurement, including early collaboration, political commitment, and a willingness to test innovative materials and methods. Crucially, they also show that when tenders include clear and ambitious criteria for environmental impact and construction time (see graph below), bio-based solutions such as wood often emerge naturally as the most viable response. Delivered through a collaborative design-and-build model, the projects reduced construction time by over 30% and exemplify how public procurement can drive circular practices and lead by example.

Evaluation criteria score

Barcelona’s housing tenders prioritise quality, environmental impact, and speed over lowest cost.

Final Thought

Embedding bio-based thinking into green public procurement is not about adding complexity; it is about aligning systems to deliver on climate, circularity, and regional development goals. Catalonia and Zeeland show that with political support, collaboration, the right tools, and strong monitoring, public procurement can become a powerful driver of change.

Download the report “Bringing bio-based into green public procurement.” Click the button below.

Source

European Forest Institute, Bioregions, press release, 2025-09-01.

Supplier

European Forest Institute (EFI)

Government of Catalonia - Generalitat de Catalunya

IMHAB Barcelona

Zeeland Province

Share

Renewable Carbon News – Daily Newsletter

Subscribe to our daily email newsletter – the world's leading newsletter on renewable materials and chemicals