Muhammad Rabnawaz, an associate professor in Michigan State University’s top-ranked School of Packaging and recent inductee into the National Academy of Inventors, has always believed that the most brilliant solution is also the simplest.

That belief is reflected in his team’s new publication in the journal Advanced Sustainable Systems.

Rabnawaz and his colleagues showed that sodium chloride — table salt — can outperform much more expensive materials being explored to help recycle plastics.

“This is really exciting,” Rabnawaz said. “We need simple, low-cost solutions to take on a big problem like plastics recycling.”

Although plastics have historically been marketed as recyclable, the reality is that nearly 90% of plastic waste in the United States ends up in landfills, in incinerators or as pollution in the environment.

One of the reasons plastics have become so disposable is that the materials recovered from recycling aren’t valuable enough to spend the money and resources required to get them.

According to the team’s projections, table salt could flip the economics and drastically reduce costs when it comes to a recycling process known as pyrolysis, which works through a combination of heat and chemistry.

Although Rabnawaz expected salt to have an impact because of how well it conducts heat, he was still surprised by how well it worked. It outperformed expensive catalysts — chemicals designed to spur reactions along — and he believes his team has just started tapping into its potential.

Furthermore, the work is already getting attention from big names in industry, he said.

In fact, the research was partially supported by Conagra Brands, a consumer packaged goods company.

A catalyst worth its salt

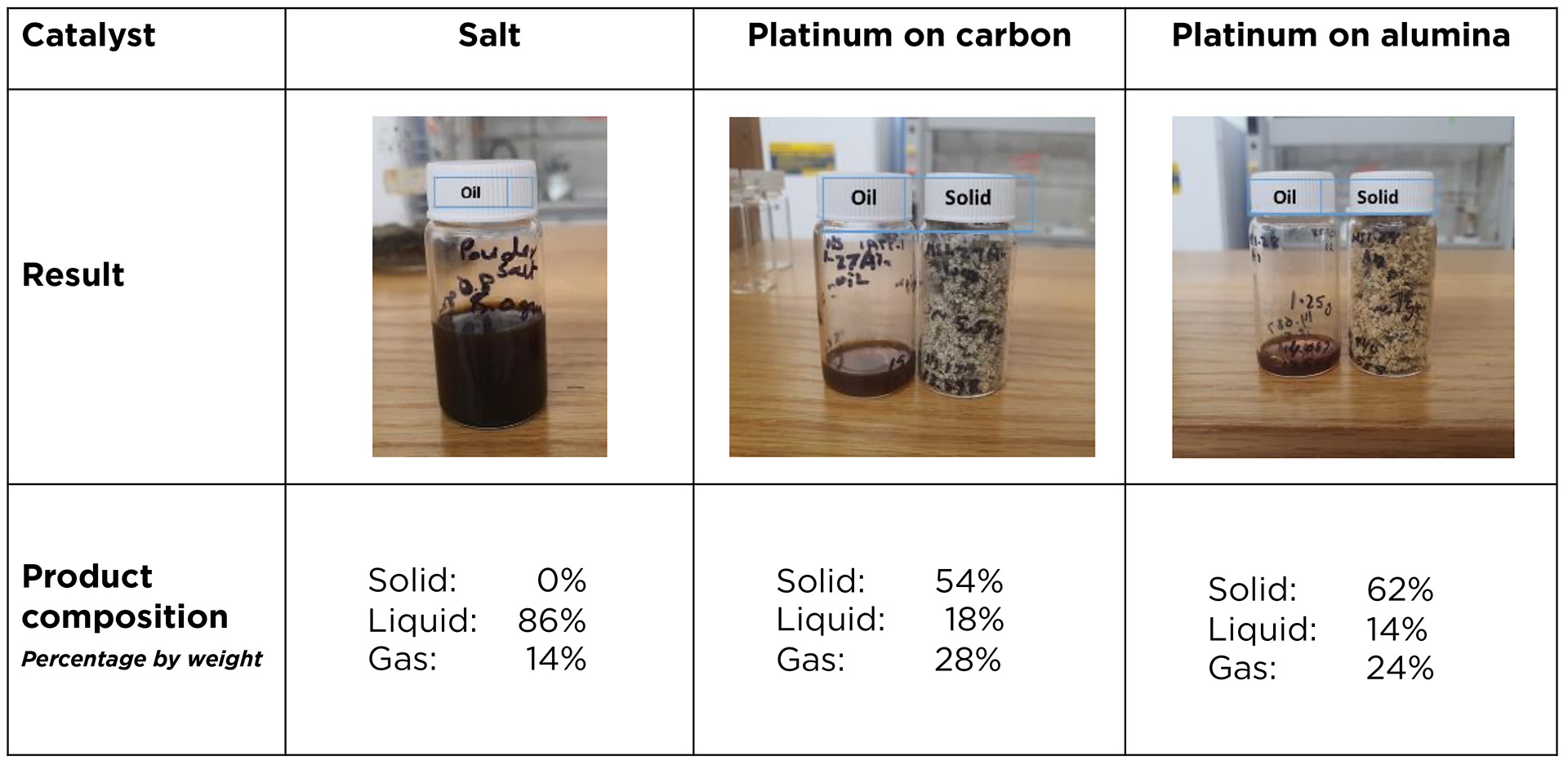

Pyrolysis is a process that breaks down the plastics into a mixture of simpler, carbon-based compounds, which come out in three forms: gas, liquid oil and solid wax.

That wax component is often undesirable, Rabnawaz said, yet it can account for more than half of products, by weight, of current pyrolysis methods. That’s even when using catalysts, which are helpful, but they often can be toxic or prohibitively expensive to be applied in managing waste plastics.

Platinum, for example, has very attractive catalytic properties, which is why it’s used in catalytic converters to reduce harmful emissions from cars. But it’s also very pricey, which is why thieves steal catalytic converters.

Although bandits are unlikely to rob platinum-based materials from a sweltering pyrolysis reactor, attempting to recycle plastics with those catalysts would still require a hefty investment — millions, if not hundreds of millions, of dollars, Rabnawaz said. And current catalysts aren’t efficient enough to justify that cost.

“No company in the world has that kind of cash to burn,” Rabnawaz said.

In earlier work, Rabnawaz and his team showed that copper oxide and table salt worked as catalysts to break down a plastic known as polystyrene. Now, they’ve shown table salt alone can eliminate the wax byproduct in the pyrolysis of polyolefins — polymers that account for 60% of plastic waste.

“That first paper was important, but I didn’t get excited until we worked with polyolefins,” Rabnawaz said. “Polyolefins are huge, and we just outperformed expensive catalysts.”

Joining Rabnawaz on this project were Christopher Saffron, an associate professor in the College of Agriculture and Natural Resources, visiting scholar Mohamed Shaker and MSU doctoral student Vikash Kumar.

When using table salt as a catalyst to pyrolyze polyolefins, the team produced mostly liquid oil containing hydrocarbon molecules similar to what’s found in diesel fuel, Rabnawaz said. Another perk of the salt catalyst, the researchers showed, is it can be reused.

“You can recover salt by simply washing the obtained oil with water,” Rabnawaz said.

The researchers also showed that table salt aided in the pyrolysis of metallized plastic films, which are commonly used in food packaging, like potato chip bags, which isn’t currently recycled.

Although pure table salt didn’t outperform a platinum-alumina catalyst the team also tested with metallized films, the results were similar, and the salt is a fraction of the cost.

Rabnawaz, however, stressed that metallized films, while useful, are inherently problematic. He envisions a world where such films are no longer needed, which is why his team is also working to replace them with more sustainable materials.

The team will also continue working to further its pyrolysis project.

For instance, the team has yet to fully characterize the gas products of pyrolysis with table salt. And Rabnawaz believes the team can improve this approach so that the liquid products contain chemicals with more valuable applications than being burned as fuel.

Still, the early returns of the team’s new table salt tactics are encouraging. Based on a preliminary economic analysis supported by the U.S. Department of Agriculture and MSU AgBioResearch, the team estimated a commercial pyrolysis reactor could triple its profits just by adding salt.

Author

Matt Davenport

Source

Michigan State University, 2023-09-07.

Supplier

Advanced Sustainable Systems - Journal

Michigan State University

National Academy of Inventors

School of Packaging (Michigan State University)

Share

Renewable Carbon News – Daily Newsletter

Subscribe to our daily email newsletter – the world's leading newsletter on renewable materials and chemicals