The most important low-carbon energy sources, renewables and nuclear, compete for investment funds. But if we are not mistaken, the dice have already been thrown in this contest of renewables versus nuclear. Renewables have won. Although it might still take a decade or more for parties involved to agree on that.

Caveats

In this article I will review electricity production costs. On renewables, I will confine myself to the most important technologies, solar and wind power. But before embarking on the subject, I should formulate a caveat, something I very rarely do. But I have seen many games played with energy production costs. I will present the case to the best of my knowledge but cannot ignore the many pitfalls that I have come across on this subject.

Projections of future energy costs depend on many methodological and numerical assumptions:

– to what extent past experiences can be extrapolated

– which elements should be included in the calculation, like project preparation, future price rises, interest (to what percentage) on loans during construction time (particularly important for lengthy projects like nuclear power station construction)

– depreciation of future investments

– fossil fuel prices in ten or twenty years’ time

– uncertainties, in technology, economics and policy

Assumptions in these areas taken together can make major differences in the outcome. Particularly if the technologies compared differ radically in size, lead times, funding and decision making process, like nuclear and renewables. It is not unfair to observe that the researcher’s opinion on (particularly) nuclear power may influence the calculation. Maybe that is only human if authors are dedicated to their subject. I may not escape the same criticism. And then, I am not even a specialist. It is with this caveat that I will present the case of renewables versus nuclear.

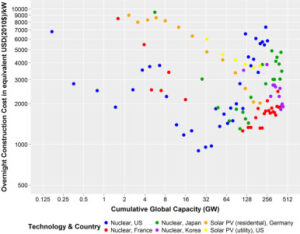

Nuclear: a negative learning curve

One of the main articles on this subject is that of Lovering et al. in Energy Policy (2016). Already five years old, meaning that the authors will overestimate the cost of renewables. They do a great job in recalculating nuclear power costs in order to be able to compare them. They discuss 349 reactors in the US, France, Canada, Germany, Japan, India and South Korea, encompassing 58% of all reactors built globally. This means they don’t look at the remaining 42%, notably not at Chinese reactors. Nevertheless, their findings are very interesting. They observe that in the initial phase, nuclear industry learns from experience and costs fall, as one would expect. But after that, some of the main nuclear countries (in particular the US, France, Germany and Canada) show a negative learning curve – over a period that now spans 50 years. Reactors get more expensive as more are being constructed. In this period, reactor prices per MW in these countries rise by 50 to 200%. India and Japan show initial prices rises and then a slow price reduction. Only South Korea experiences a constant price reduction over 50 years, less than 1% annually. South Korea is a country with a strong nuclear industry, building a standardized design. In short: there is no clear price development over the past 50 years, certainly no reduction.

What happened? We need to take into account that from the 70s onwards, nuclear power experiences severe criticism as to its safety. And then, in the 70s and 80s some major accidents with nuclear reactors happen: Three Mile Island (1979) and Chernobyl (1986). As a result, nuclear reactors are redesigned continuously in order to provide better safety.

As Joe Romm puts it: ‘New reactors are intrinsically expensive because they must be able to withstand virtually any risk that we can imagine, including human error and major disasters. Why? Because when the potential result of a disaster is the poisoning (and ultimately, death) of thousands of people, even the most remote threats must be eliminated.’ This eventually translates into real-cost escalation, or ‘negative learning’ (in terms of learning curve models). Exacerbated by the technology scale-up, intended to score economies of scale, but inevitably increasing systems complexity, reversing the cost learning curve. As Romm phrases it: ‘new nukes have gone from too cheap to meter to too expensive to matter for the foreseeable future.’ And recent history shows major disappointments like the 1,600 MW Areva reactor in Olkiluoto (Finland), now delayed by 13 years already and still under construction.

Renewables versus nuclear: the comparison

In their article, Lovering et al. compare nuclear and solar PV costs, see graph. But I have a problem with their comparison. For nuclear energy, they rate ‘overnight construction costs’, typically accounting for roughly 55% of total costs. OCC includes direct engineering, procurement, and construction (EPC) services, and indirect costs like project management. The authors focus on OCC because these are so unpredictable; the other cost components – interests, O&M, fuel, and provisions for decommissioning and used fuel storage – tend to have much less variation. Fair enough. But as an illustration of my caveat, if I am not mistaken, the solar PV costs they take from another source are total costs. They don’t just include panel costs, but also customer acquisition, installation labour, profit/overhead costs, and expenses related to permitting, interconnection, and inspection procedures. If I were right, we need almost to double nuclear costs shown in the graph. We need to make sure that we don’t compare apples and pears!

In addition, we need to take into account that wind and solar energy costs keep coming down. In shorthand, in the Conversation: globally, renewable energy generation doubled in the five years to 2020, from under 20 gigawatts in 2014 to 41.2 gigawatts in 2019. The quoted price for solar electricity fell almost 20% in the first six months of 2020 alone. August 2020 saw the world’s lowest-ever solar power auction.’ And the authors note: the cost of offshore wind and energy storage has fallen rapidly; so rapidly in fact that they doubt that the licence for UK’s Hinkley Point C nuclear power station, granted in 2010, would still be granted today.

Renewable costs falling fast

So here is the case as far as I can fathom it. Both solar and wind power can now generate electricity at $ 0,05 – 0,11. At these prices, they have become competitive to fossil-based electricity production. Historic figures show costs that come down quickly. In Germany for instance, a very average country pricewise, solar PV costs have come down by 73% since 2011 and wind energy costs by 37%. All these figures from the site of IRENA, the International Renewable Energy Agency. As both solar and wind technologies are still in full development, it is reasonable to assume that their prices will keep on falling for some time. Although adapting the electricity system to them may incur new costs that we would have to take into account.

And where does nuclear power stand in this competitions of renewables versus nuclear?

– Nuclear power costs have become quite unpredictable in many countries. Only standardized reactor systems seem to be able to produce prices that fall over time.

– Even if nuclear power were cheaper than fossil-based power, it would have a hard time to compete with renewable energy sources that still become cheaper each year.

– It is of major importance to bring down CO2 emissions fast. With that in mind, it is important to note that lead times for renewables are very short. A major wind farm can be constructed in 6 months – decision making and paperwork will take up most of the time of the project. For solar power, lead times are comparable. For nuclear power, construction time easily tops 10 years, and add at least another 5 years for decision making and permits. By then, the fast-developing renewables will easily have outperformed nuclear. Both in price and in CO2 reduction.

And that leads us to the conclusion formulated in the opening paragraph: renewables have won already. If I am mistaken, I would be glad to hear the arguments.

In two articles, we compare the two most important low-carbon energy sources: nuclear and renewable energies. The articles were published on January 18 and January 23, 2021.

Author

Diederik van der Hoeven

Source

Supplier

International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA)

Share

Renewable Carbon News – Daily Newsletter

Subscribe to our daily email newsletter – the world's leading newsletter on renewable materials and chemicals