One of today’s economic bestsellers is Doughnut Economics, written by the British economist Kate Raworth. Her book is an outright attack on the dominant neoliberal economic theory. Permanent growth is impossible! In growing permanently, we will transgress social and ecological boundaries! I saw her on TV and right away asked myself how her project could be successful without a proper understanding of today’s technological developments. For technology is a terra incognita for Raworth. Like for most economists. Which in the end lends a strong Malthusian flavour to her opinions.

The principle of doughnut economics

The principle of doughnut economics

Doughnut Economics is one of those well-written and also scientifically well-founded books that make you wonder why its opinions are so self-evident. Although being critical of its contents from the start, I appreciated reading the book very much. Raworth also is a gifted speaker, good at drawing people into her mind-set. In her book she starts quoting the people who laid the foundation for economics, economists not yet infected by fashionable neoliberal views. And she points out the obvious, that companies and governments should broaden their goals far beyond the realms of money making and economic growth, in order to fulfil very down-to-earth social demands from the majority of the population.

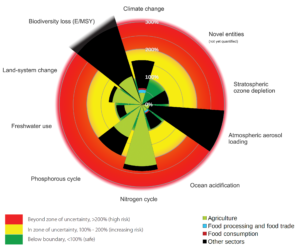

In her image of the doughnut, Raworth concurs with the concept of ‘planetary boundaries’ proposed in 2009 by Johan Rockström and 28 of his scientific colleagues, in an article in Nature. The authors propose the existence of 9 planetary boundaries that mankind should not transgress in order not to endanger the Earth’s resources. In Raworth’s image of the doughnut, the inner empty space represents human poverty and hardship – a space that we should outgrow. The doughnut itself is mankind’s safe and fair space. Outside is the area of critical planetary degradation. But hey, don’t we discover the spirit of our old friend Robert Malthus in this concept of planetary boundaries? The idea that the Earth’s resources are limited, and that these will be harmed fatefully by increasing human activity – be it by a growing population, like in Malthus’s philosophy, or by economic growth, like in Raworth’s book Doughnut Economics, and much earlier already in the Limits to Growth report?

Moving boundaries

Malthus’s basic concept – limited resources will always be depleted in the end if mankind would continue using ever more of them – is very simple and convincing. The real enigma that surrounds economic growth, therefore, is why this depletion never happens in reality. But this question appears not to be popular. Even though there is a very simple answer to it: boundaries move as a result of technological developments. During the past two centuries, mankind has used its smart thinking again and again for the development of new solutions. This also constitutes the short answer to the question why none of the expectations of the Limits of Growth report has ever materialized. Nevertheless, the concept of planetary boundaries still exerts a special attraction. Rightly so, insofar as it appeals to the notion that we should treat our natural heritage responsibly; undeservedly so, insofar as this concept shields us from a clear view on the most productive move to shift the boundaries: investing in mild technologies. Or, as we formulated it in our book More with Less: in precision technologies – technologies that enable us to produce exactly what we wanted to, but that have no non-productive side effects. On that basis we coined the term precision economy, which in every respect seems to be better than the dull term doughnut economics.

Because the author of Doughnut Economics has a very limited view on technological developments, the book abounds with economic policy measures that mankind should take; Kate Raworth does not formulate technological developments targets, like support to precision technologies. Even so, many of her insights appeal to me. Like: leave behind us the thought that economic growth will solve most social problems, from unequal income distribution to environmental pollution. Raworth also shows that the cleaner economy, a consequence of economic growth according to neoliberal economists, is partly a matter of perception, based as it is on the export of unpleasant activities to developing countries. And in chapter 6 she supports biomimicry; but as an economist, she mainly conceptualizes it in economic terms: supposedly based on a new concept of value. It escapes her that beneath this, there is a technological revolution towards soft technologies going on.

Because the author of Doughnut Economics has a very limited view on technological developments, the book abounds with economic policy measures that mankind should take; Kate Raworth does not formulate technological developments targets, like support to precision technologies. Even so, many of her insights appeal to me. Like: leave behind us the thought that economic growth will solve most social problems, from unequal income distribution to environmental pollution. Raworth also shows that the cleaner economy, a consequence of economic growth according to neoliberal economists, is partly a matter of perception, based as it is on the export of unpleasant activities to developing countries. And in chapter 6 she supports biomimicry; but as an economist, she mainly conceptualizes it in economic terms: supposedly based on a new concept of value. It escapes her that beneath this, there is a technological revolution towards soft technologies going on.

The doughnut economy is not a closed system

In chapter 2, Kate Raworth opposes the supposition of economic model builders that the economy would be a closed system. OK! But in the very same paragraph, she nevertheless takes the earth itself to be such a closed system: solar energy does pass through the earth’s system, but matter can only circulate within the system (and here, she quotes Herman Daly, who makes the same mistake). It is remarkable that she observes the sun’s contribution, but does not grasp how this would fundamentally alter her position.

Because of the very contribution of solar energy, the earth is not a closed system: the sun endows the earth with thousands of times more energy than we need to keep the economy going. Many economists will retort that the sun does not provide materials for us. But even there, they would be wrong. The mere production of agricultural waste amounts to 7 billion tons annually, whereas the entire chemical industry produces less than 1 billion tons. In the course of time, even many applications of metals can be substituted by biobased polymers. But the only application of biomass mentioned in Doughnut Economics is that of energy supply. The book therefore does not mention the biobased economy, unlike the circular economy.

In short: a fine book, Doughnut Economics. But it would even have been much better with some understanding of the technological revolutions of our times; no, not ICT, but chemical catalysis, biotechnology, useful applications of agricultural side streams, precision technology in general. That would have bridged the artificial gap, drawn in the book, between corporate moneymaking and the lofty goals of the doughnut economy. For an interesting characteristic of precision technologies is that companies apply them in pursuit of their own economic goals, whereas their application supports social and ecological goals at the same time.

Kate Raworth. Doughnut economics. Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st century economist. ISBN 9781847941374.

Author

Diederik van der Hoeven

Source

Share

Renewable Carbon News – Daily Newsletter

Subscribe to our daily email newsletter – the world's leading newsletter on renewable materials and chemicals