The Conversation informed us about the negotiations on a global pact on plastic. A penultimate round of negotiations recently ended in Ottawa – the last stage will take place later in November in South Korea. Countries agreed that they should tackle plastic pollution at every stage. Writes Jack Marley, Environment commissioning editor. But a proposal by Rwanda and Peru to cut plastics production by 40% in 2040 was turned down.

Ambition level

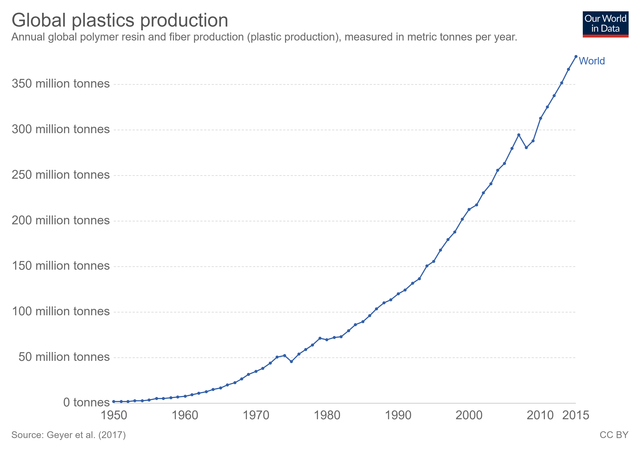

Nevertheless, a recent study showed that the most effective way to cut pollution is to reduce plastics production. Rather a no-brainer, it would seem. But this concept was fought by the representatives of plastic producers, and of the oil and gas industries.

It’s now unclear what an agreement will look like. It could be ambitious, ‘with strict binding measures focusing on all stages of the plastics life cycle (including the upstream stages associated with resource extraction, manufacturing and processing),’ according to researchers Antaya March, Cressida Bowyer and Steve Fletcher, of the University of Portsmouth. Or it could be weaker, ‘with voluntary and country-led measures that focus mainly on waste management and pollution prevention (the downstream stages).’

Petrochemical companies’ strategy

Petrochemical companies have long insisted that downstream strategies are the best way to manage plastic waste; like better and more intensive recycling. But evidence shows that companies involved in plastics production knew for a long time already that recycling is complicated, expensive and ineffective. Although they did not (and still do not) communicate this knowledge.

The result of this non-communication is a trade in plastic waste between developed and developing countries, with the latter being at the receiving end. Developed countries have not developed the technology to deal with plastic waste – and of course, neither have developing countries. As the waste arrives, waste pickers search the imported refuse for plastic bottles and other recyclable items. These are low-paid tasks, mainly performed by women. Typically, the remainder will be burned. The toxic fumes from this open burning result in a health crisis, write Costans Velis and Ed Cook.

Developing countries pay the toll

In developing countries, any existing recycling facilities are overburdened. Moreover, environmental regulations tend to be weaker. But typically, difficult to recycle plastic waste is now being diverted to the same developing countries.

Oil and gas companies tend to look upon plastics as a market that will continue after oil and gas demand will fall. Plastics production, like fossil fuel extraction, profits from fossil fuel subsidies. How then should we curtail plastics production if oil and gas production would diminish? Recent calculations show that from now on, oil and gas production need to fall by 2.5% annually – and even by 5% from 2030 onwards. But does this happen? Jack Marley is of the opinion that this should be done by a legally binding agreement, to be concluded at the final summit in Busan, South Korea in late November.

Combined effort

And even this might not be sufficient. We have examples of climate legislation, supposedly ‘legally binding’, that were only enforced in court. Where environmental groups took their cases, in order to make governments keep their promises.

All in all, curbing plastics production will require a combined effort. Campaigners should closely work together with campaigners on climate change, says Jack Marley. As long as fossil fuels are cheap and abundant, curbing plastics production will have to result from legal and public action.

Author

Diederik van der Hoeven

Source

Supplier

The Conversation

University of Portsmouth

Share

Renewable Carbon News – Daily Newsletter

Subscribe to our daily email newsletter – the world's leading newsletter on renewable materials and chemicals