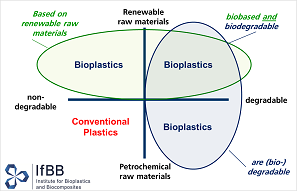

The term bioplastics causes much confusion and will continue to do so, according to my conviction. The public does not seem to grasp the difference between bio as in biobased and bio as in biodegradable. As the plastic soup problem tends to become more important than the non-fossil origin of plastics, bioplastics come under fire because most of them are not biodegradable. It is high time to divide plastics into two distinct groups: the biodegradable plastics on the one hand, and the plastics that are recycled on the other hand. Insofar the latter plastics enter into an open, non-industrial system, people will have to pay a deposit for them. Or the producer will have to remain the owner and be responsible.

On 31 March 2017, the Dutch quality program Nieuwsuur had an item called ‘Chaos in bioplastics land’. The interviewees were a representative of the Plastic Soup Foundation, a representative of a waste treatment company, and a Wageningen UR researcher. The first two voiced the program’s message: the so-called bioplastics are useless, because most of them are not biodegradable. Bioplastics keep on adding to the discharge of plastics to the oceans, and in waste treatment they cause much confusion, the reason why many non-degradable plastics are discharged in the green bin. Remarkably, not even half a minute of the program was reserved for an explanation of the difference between biobased and biodegradable. Each of the experts could have done it, but apparently the editors saw no reason for such an explanation. Consequently, we presume that the ‘chaos in bioplastics land’ is predominantly in their heads. For the innocent viewer, the main message was: ‘we should keep producing plastics from fossil sources’. Weird!

Bioplastics in open and in closed systems

Bioplastics industry might tend to conclude that they need to inform the public more adequately, but we could also draw another conclusion. Researchers and industry not having been able to communicate a clear picture for twenty years now, there is every reason to believe that they will never succeed in this. It is high time therefore to change course. In order to solve the plastic soup problem, all non-biodegradable plastics will have to be recycled. In an industrial setting, this is a straightforward operation – and insofar plastics recycling is not properly done, it should be enforced by law. The problem is in the plastics that end up in an open system: with the consumer.

Recently, we published an interview with Joan Hanegraaf, CEO of the major plastic processing company Oerlemans Packaging. According to Hanegraaf, there is just one solution to the problem of plastic litter: strict laws and ditto enforcement. Biodegradable plastics – they are produced with good intentions, says Hanegraaf, his company tries to sell them for twenty years now, but they still make up just 1% of total sales. In some applications, they have decisive advantages, like Pharmafilter’s bed-pans and Rodenburg’s plant pots, that are the key to better management systems, but in general precisely the non-biodegradability of plastics is their key characteristic. We would not like to see our beverage slowly eating away its encapsulation! The leakage of ‘open system’ plastics to the environment, says Hanegraaf, should be dammed by deterrence: legislation and enforcement. Look at Singapore.

The stick AND the carrot

But in many instances, deterrence is supplemented by benefits, and for good reason. Human behaviour is best guided by the combination of the two. We can accomplish that by charging a deposit on plastics that enter into the open system. Which would render profitable their return. Plastic bag? Biodegradable or a deposit! Plastic consumer goods packaging? Either the retailer will be responsible for the return, or the consumer will pay a deposit, or the packaging will be biodegradable! Even if there could be a problem because of the general rule that deposits should be lower than production costs, in order not to tempt producers to produce just in order to cash the deposit.

This will require a major reorientation of the plastics industry, and of commercial plastics users. But surely this could be done in ten years’ time. Industrial countries should take the lead – but this task is not beyond any country’s capabilities. Bioplastics will have to prove themselves by other means: by better quality, by new functionalities, or by real biodegradability. For in my terminology, ‘biodegradable’ does not mean: biodegradable in an industrial composting equipment, at 60 °C and a supply of the right enzymes. No, let’s end confusion: biodegradable means that the plastic will be degraded to harmless substances like H2O and CO2, in the soil or in open water. Which will finally create two distinctly separated plastics cycles: plastics that will be recycled, and plastics that will be degraded in the environment. No more confusion. Then, even quality programs should have no more reason to be confused.

The circular solution

And there is another viable solution. The German/Dutch architect Thomas Rau is a long-time proponent of circular solutions, in which the producer remains the owner of the product, and is therefore charged with the responsibility for proper end-of-lifetime solutions. We can also apply this principle to plastics. Plastics producers would then become responsible for their product during its entire lifetime by civil, penal and fiscal law. We would see them all of a sudden exerting themselves to the utmost to find solutions for plastic littering. Paint producers would still be the owners of the paint on the consumer’s window sill. In no time they would know how and when to serve the consumer to remove the old layer and apply a new and better one. An extra challenge in this cycle would be to develop a benefit from the ageing product. The paint on the sill should not deteriorate but improve during its lifetime; it should develop a new functionality beneficial to a new application. We could also consider the graphite electrodes in car batteries, that can become so thin that they can serve as the resource for graphene in nanocomputers. Lots of challenges for product designers and engineers!

Author

Alle Bruggink, Diederik van der Hoeven

Source

Supplier

Oerlemans Plastics

Pharmafilter (NL)

Plastic Soup Foundation

Rodenburg Biopolymers B.V.

Thomas Rau

Wageningen University

Share

Renewable Carbon News – Daily Newsletter

Subscribe to our daily email newsletter – the world's leading newsletter on renewable materials and chemicals